After a round of introductions of all people present at the conference at 8:00 AM on Tuesday, February 4, the first session, Managing Pastures in Riparian Areas for Water Quality and Forage Utilization began. Dr. Les Vough, UMD Forage Crops Extension Specialist Emeritus, was the moderator.

Dr. David Butler, Assistant Professor of Organic, Sustainable, and Alternative Crop Production, University of Tennessee, was the first presenter. The title of his presentation was Ground Cover Impacts on Nitrogen, Sediment, and Phosphorus Export from Simulated Rotational Grazing in Riparian Areas. With pasture at the stubble height of 4 inches (10 cm.) and canopy cover of 65 percent or higher, he found runoff losses of nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and sediment (S) to be very low in the small runoff plots over a 6-month period with 2 applications of feces and urine (to mimic 4 cows per hectare per year application rate) and 4 rainfall simulations at 70 mm (2.8 in.) per hour for 1 hour.

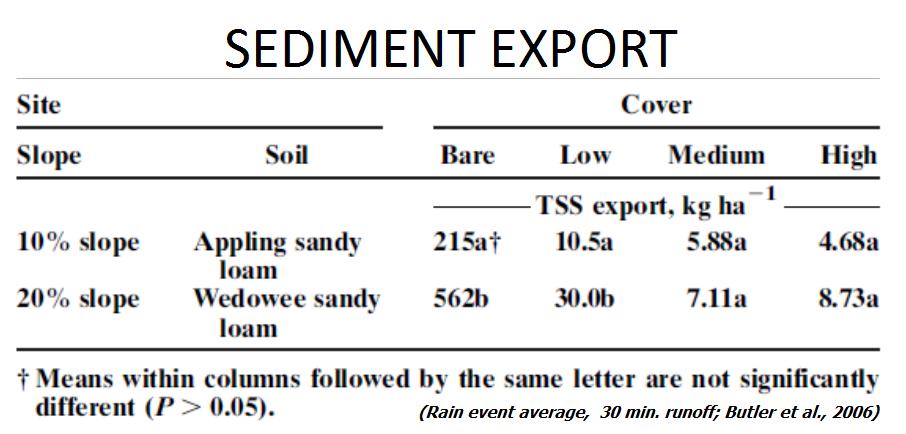

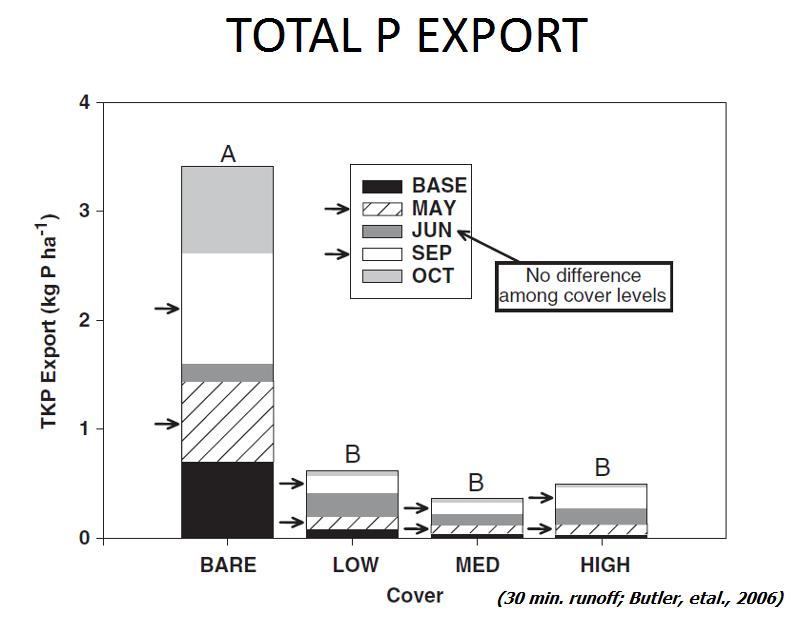

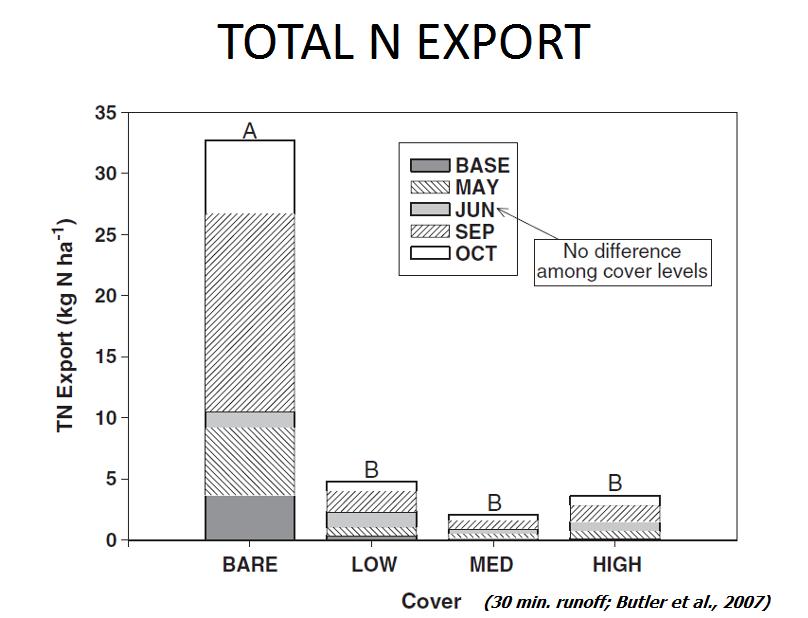

Nitrate losses were 2 kilograms/hectare (kg/ha), P export was 0.5 kg/ha or less, and sediment loss was 10.5 kg/ha or less on a 10% slope (Editor notes: This slope is much steeper than those encountered on bottomland pastures; losses would be even lower there unless flood overflows occurred. On a simulated heavy use area that can develop for real under shade in pastures, the ground was essentially bare and the soil heavily compacted, the losses of N, P, and S were much higher.

Heavy use areas are likely to occur along the exclusionary fence where streams are fenced off from pasturing livestock and brush and trees invade to replace the grass in the exclusion area. Once the trees reach pole-size diameters, they cast shade and livestock will be attracted to the shade to avoid the intense sun of mid-day.) In these simulated heavy use areas, total nitrogen export was 33 kg/ha on a 10 percent slope versus less than 5 in the grassy plots, total phosphorus was 3.5 kg/ha versus 0.5, and total sediment export was 215 kg/ha versus between 4.68 and 10.5 kg/ha on the grassy plots.

Since the exclusion area is often kept to a minimum to avoid loss of significant pasture ground, the heavy use area will be within a few feet of the water’s edge of the stream with little to no ground cover to filter out any of the 3 pollutants studied by Dr. Butler and targeted by the Chesapeake Bay Program for reductions to restore Bay waters.

The unintended consequences could be much worse than an occasional direct deposit of dung or urine directly into the stream by livestock getting a drink or crossing the stream. It all depends on the amount of time livestock spend within the stream and its immediate banks and whether or not the pasture is actively managed by the farm operator to provide a protective ground cover and adequate residual stubble heights of 3 or more inches.

Dr. Butler’s conclusions were:

- Cattle feces and urine in riparian areas can contribute nutrients to

surface waters, but good cover can minimize impact.

45% ground cover (\~65% canopy cover) is similar to 70% - 95% ground cover for reducing nutrient export from cattle feces and urine in well-drained soils. - Timing of rainfall in relation to manure deposition is an important factor.

- Greater export of dissolved reactive P and ammonia-N immediately after deposition

- Runoff nitrate is less affected by timing

- Lounging or heavy use areas in the riparian zone can export significant amounts of sediment and nutrients.

- Maintaining cover can help minimize impact of riparian grazing to surface waters.

- Rotational grazing systems which minimize livestock time near surface waters and maintain cover may be an effective management strategy.

More work is needed to evaluate management of these systems at the farm-scale for stream water quality impacts.

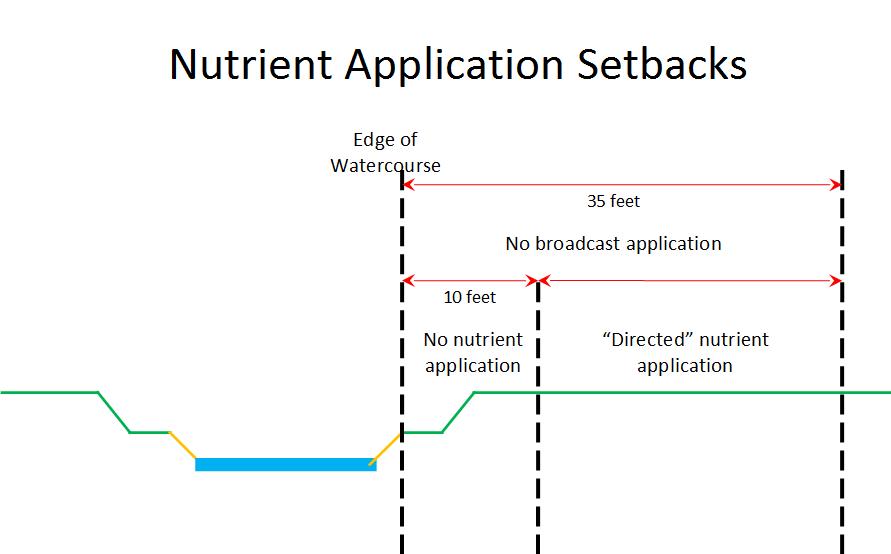

Dwight Dotterer, Nutrient Management Program Administrator for the Maryland Department of Agriculture (MDA) was the next presenter. The title of his presentation was NEW Nutrient Management Regulations Relating to Setbacks for Streams. MDA in May of 2012 issued new nutrient management regulations that gave stream setbacks to be adhered to on both cropland and pastureland. These regulations became effective January 1 of 2014. Pastures and hayfields are subject to a 10-foot setback. This would require some type of fencing, either permanent or temporary portable fences. Nutrients may not be applied mechanically within the setback. Livestock shall be excluded from the setback to prevent direct deposition of nutrients within the setback.

However, as an alternative to fencing livestock from the setback area, a person shall work with the soil conservation district to develop and implement a Soil Conservation and Water Quality Plan for their farm with the local soil and water conservation district office with (BMPs) such as stream crossings, alternative watering facilities, grazing management plan, or other MDA-approved BMPs. This plan must be documented and followed in order to be in compliance.

As another alternative to a nutrient application setback, MDA may approve other BMPs that it finds equally protective of water quality and stream health. MDA will work with USDA-NRCS, University of Maryland, or other land grant universities to establish the effectiveness of these practices. When livestock must access pasture on both sides of the stream, stream crossings must be designed and constructed to prevent erosion and sediment loss.

In the practical application of the Maryland nutrient regulations, flash grazing might be an alternative. MDA will be discussing this option as a component of a grazing management program for a farm.

- Fencing - MDA does not require permanent fencing; temporary electric is fine.

- Alternative BMPs? MDA suggests you consult the local SCD. Any BMP that the farmer and the SCD agree could work can be installed. But, it must work. If alternative BMPs do not prevent animal access, fencing may still be required.

MDA has had a memorandum of understanding with the MD Department of the Environment (MDE) since 2000 to provide joint inspections of farms when a citizen complaint alleging a water quality violation is received by MDE. This is a complaint driven process - this will probably be MDA’s biggest priority, we are obligated to respond. However, checking will also occur during random Implementation Reviews: MDA and MDE may end up walking streams. They will be anxious to evaluate alternative BMPs for effectiveness.

To assist farmers with complying to the new nutrient management regulations, the Maryland Agricultural Cost-Share Program does provide funding that can cover up to 87.5% of the cost to install certain agricultural BMP’s including stream fencing, stream crossings, watering troughs, spring developments and water wells to exclude animals from streams. Beginning July 1, 2013, a newly funded practice was announced that provides up to 87.5% of the cost to establish a pasture to be used within a management intensive grazing system or to convert or renovate a pasture previously used for continuous grazing. The maximum allowed for this practice is \$50,000 per farm.

Patricia Engler, State Resource Conservationist, USDA-NRCS, from Annapolis, MD was the last speaker for this session. Her topic was Cost-Share and Technical Assistance Programs to Help Maryland Farmers Implement New Pasture Nutrient Management Regulations in Riparian Areas. NRCS structural conservation practices, such as fencing, require a 20-year life span to receive cost-share assistance from NRCS financial assistance programs. However, with the Prescribed Grazing practice, a nonstructural conservation practice that may have several components with shorter estimated lifespans (e.g., portable electric fences and water troughs), it can be cost-shared through NRCS.

It is a management practice rather than a structural practice. In order for it to continue to be effective, the operator must constantly monitor and make decisions to provide proper forage allocations and water to the live-stock and on when to move livestock to the next paddock allocation of forage so as to keep the forage resource thriving (leaving an adequate residual stubble height after grazing event) and meeting livestock performance goals given the circumstances of weather, time of season, and forage species present.